BCHS Blog

Read all about BCHS’s recent findings below.

Summer Programs 2023

Click the link below to view the Summer Programs for 2023!

Spring 2023 Newsletter

Click the link below for the Spring 2023 Newsletter!

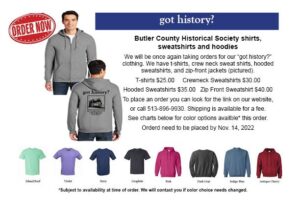

BCHS Shirt Sale

The Butler County Historical Society is selling t-shirts, crew neck sweatshirts, hooded sweatshirts, and front zip sweatshirts. Orders will be picked up at the Historical Society at 327 N. Second St. Hamilton, OH 45011 the beginning of December. Orders must be placed by Nov. 14, 2022. Delivery available for a fee (please contact us to make these arrangements prior to ordering any items). You may click the links below or call us at 513-896-9930 to place your order. Payment is due at the time of order. If you have any questions, please reach out to Christina at [email protected]

The Butler County Historical Society is selling t-shirts, crew neck sweatshirts, hooded sweatshirts, and front zip sweatshirts. Orders will be picked up at the Historical Society at 327 N. Second St. Hamilton, OH 45011 the beginning of December. Orders must be placed by Nov. 14, 2022. Delivery available for a fee (please contact us to make these arrangements prior to ordering any items). You may click the links below or call us at 513-896-9930 to place your order. Payment is due at the time of order. If you have any questions, please reach out to Christina at [email protected]

Summer 2022 Newsletter

Summer programs, Model T’s and more! Click the link below for our Summer 2022 Newsletter

Spring 2022 Newsletter

Summer Programs, Quilt Exhibit and more!

Click the link below for the Spring 2022 Newsletter.

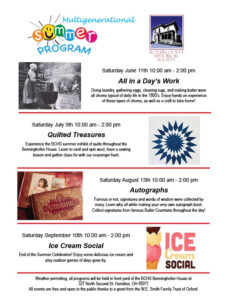

2022 Multigenerational Summer Programs

The 2022 Multigenerational Summer Program Dates have been announced. These programs will be held outside (weather permitting) in the front yard of the Benninghofen House. All programs are FREE and open to the public, thanks to a grant from the W.E. Smith Family Trust of Oxford.